Terraforming

Or why the last 14 years of Conservative Government did accomplish something

What makes a political leader truly successful? Arguably, it is their capacity to permanently alter their country’s political landscape. To terraform it, if you will. This is not the same as getting the opposition to accept a given policy. For instance, the fact Labour has (currently) accepted Hunt’s National Insurance cuts does not count. To qualify they must be big changes. So systemic that they change our politics. That they change what is politically conceivable. They must significantly shift the Overton Window.

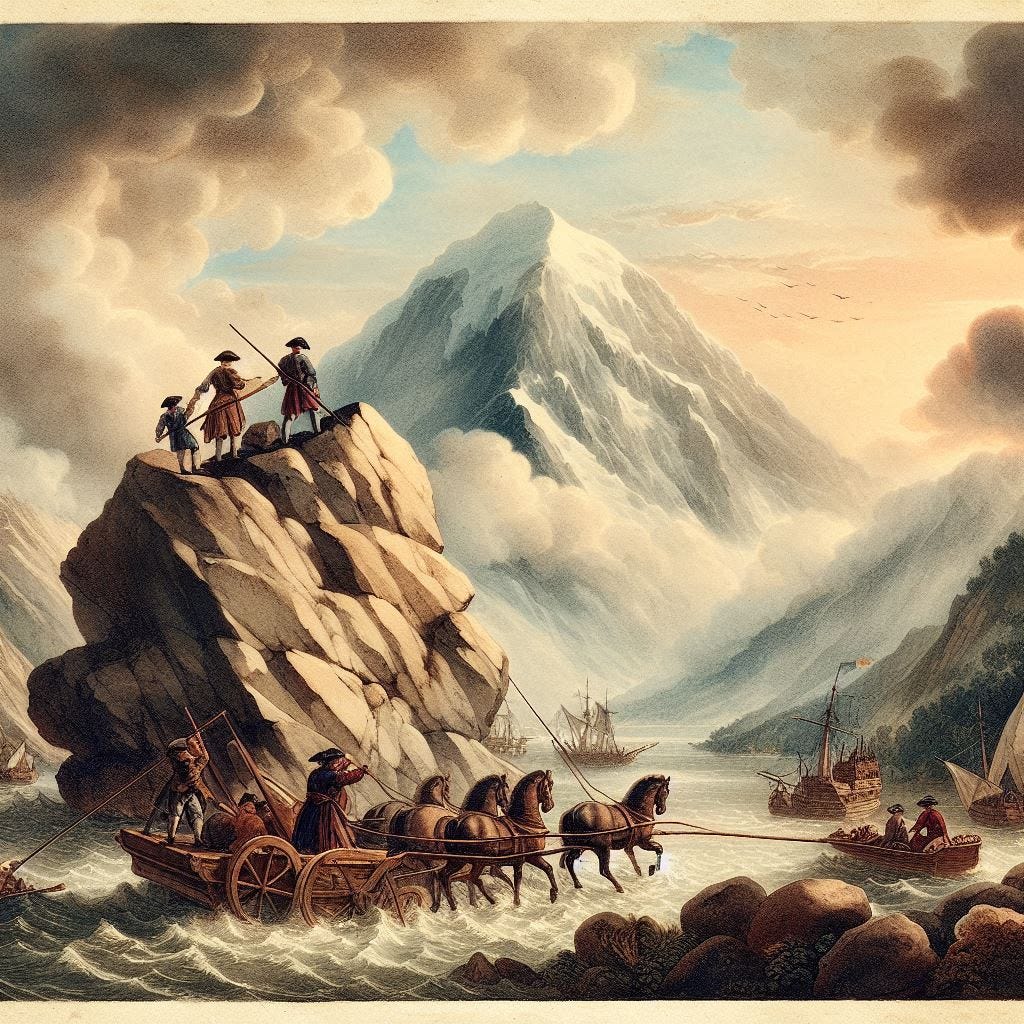

Thatcher and Blair are trite examples of leaders who managed to do this. Your car is not made by a state-owned company. The council is not your landlord. The House of Lords is a shadow of even its post-Parliament Acts former self. The words ‘Judicial Review’ strike fear and dread into the hearts of ministers. These leaders moved the mountains and rivers of our politics.1 They made it so that their opposition could not win until they adapted to the new environment

.

It is a popular idea amongst British conservatives that the last Tory government utterly failed to do this. Indeed, some even complain that the Conservative Party serves only to conserve the previous Labour government’s consensus, but never to undo any of it. In essence, that it achieved nothing, or worse yet: nothing conservative and right-wing. That it managed merely to arrest – but never stop – the march of ever more progressive policies through the British state.

Some of this sentiment is just a natural reaction to losing power – and it will pass. The loss is too recent. It hurts too much still.

Nonetheless, some – indeed much – of this sentiment is getting at something true. The Tories did not roll back the Blairite Administrative State: the Human Rights Act, the Supreme Court, the Equality Act. All of these survived the last 14 (or 10) years of Tory government unscathed. In fact, in the case of the Human Rights Act it survived the threats of repeal contained in the 2015 Tory manifesto and of updating in the 2017 and 2019 manifestos.2

It would be even harder to argue that the Conservative Party has turned back the clock to the way things were before 2010 or 2015. Indeed, their only achievement which enjoys broad support is the introduction of Gay Marriage. One might think it was a good policy (I certainly do), but it’d be Campbell-grade spin to suggest it was somehow a particularly conservative thing to do.

To add insult to injury, the new Labour government seems not to feel itself so constrained. Imagine the frustration of many a tory when it was announced that the new Labour government will seek to repeal the Strikes (Minimum Service Levels) Act 2023. They can do it but for reason we cannot.

There is undoubtedly something here. The phenomenon is real. Tories seem unwilling to reverse changes or oppose things they could probably get away with revising or opposing. See, for instance, the section 35 order that stopped the Gender Recognition Reform (Scotland) Bill. The received opinion before the order was made was that making an order would precipitate some constitutional calamity or at the very least would tear at the fabric of the Union. What happened? The SNP lost its most successful politician and nationalism has not looked so weak in ten years.

Nonetheless, this widespread despair is misplaced in two key respects: one small and one large. First, it is no good complaining about it now. The battle was lost in 2010. The reality is we did not get enough seats in that election to justify a wholesale unwinding of Blairism. That is why he is a terraformer and say David Cameron is not. Cameron had to accept Blairism to succeed him. True, maybe, just maybe we could have gotten away with moving one or two small mountains. For example, we certainly had an (unexpected) mandate in 2015 to repeal (and replace) the Human Rights Act. Why did we not do that? Well, that take me to the second, large, point…

It is simply not true that the Tories failed to terraform Britain’s politics over the last decade. Or had you forgotten about Brexit?

Do not worry, dear reader. This is not some gloating piece on the ills of Brexit. You have read it all before and anyway, that is not my view.3 Instead, the point here is just to note that we cannot exactly complain that we got nothing done. We did. We took the UK out of the EU. Not only that, but it is totally uncontentious now. It has moved to become part of the accepted political framework a government has to operate under.

For instance, the 2024 Labour manifesto does not mention Brexit once. The Liberal Democrats, which you might expect to both be the least pro-Brexit and to feel less constrained in what they say, safe in the knowledge that they will never need to implement it all, mention it twice. Just twice. Once as a passing jab when talking about the Environment; we can ignore that. The other time more, more substantively, when talking about the Economy. But when I say ‘more substantively’ it is still blink-and-you-miss-it. They blame the Tories’ ‘botched Brexit deal’ for damaging the economy. And the solution they propose? Repairing ‘the broken relationship with Europe’. Hardly an arch-Remoaner position, is it? The party that once wanted to turn back the clock and reverse Brexit wholesale has accepted that we are out, that rejoining is not a viable political proposition today and that the best they can hope for is to signal their Europhile vibes with vague references to improving relations.

In this sense the politics of 2024 are (unimaginably) more conservative than they were in 2014. What was then a fringe position on the right of British politics – that we should (or even could!) leave the EU – has, primarily as the result of the efforts of some in the Conservative Party, become not only reality, but so accepted that even we right-wingers take it for granted.

What are the lessons from this? Perhaps only two: First, the rather basic one that doing controversial things is difficult – and can cause your party to implode… Political things cost political capital and we decided in 2016 to spend ours on Brexit. It was such a big expenditure, that it left us with little for anything else – although of course Covid then took its fair share too…

Second, that while political terraforming necessarily involves victory for a political movement or idea, it does not necessarily mean that those implementing it will stay on forever. After all, both the Thatcherite Revolution and the Blairite Administrative State outlived the political lives of their creators – and quite quickly too! The world moves briskly on, and God did things move briskly in 2020. But it was always hubris to expect that those who gave us their votes on loan in 2019 would be happy to continue the loan on favourable terms (or at all) when it matured in 2024.4

A final thought: seeing as we did achieve this massive political success, why are we not happy? It would be easy to say that it is just because we lost the election (which really has very little to do with Brexit, in my opinion). But that cannot be the whole explanation, surely? If it were, we could be disappointed, even angry, at losing power but content at having moved a pretty big mountain. Instead, like a child who begged and stomped that he wanted a toy, we seem to have forgotten all about Brexit after finally getting it.

A full answer to this question is best left for another time. But the answer may well be that the Tories do not have a coherent vision for what Conservative Britain looks like, let alone what a post-Brexit Conservative Britain looks like. Or, as the ever-thoughtful FurtherOrAlternatively has put it, neither the Conservatives (nor indeed Labour, but that also is a matter for another day…) seems able to articulate what their Political Promised Land looks like.

1 And it is no coincidence that the resulting topography was easier to traverse for its creators. Homeowners with mortgages turn Tory quite quickly after all…

2 The fact that Cameron’s manifesto is decidedly more extreme on this illustrates that perhaps BoJo was not an extremist, he was just unsuited to government.

3 My Spanish relatives are tired of hearing how well we Europeans were treated by HMG and how badly the EU treated brits.

4 And that is before considering the effects of Covid and our incompetence.